Why don't I feel emotional about most of the code I write today?

A few days ago, my colleague Adam Witkowski published an interesting article titled ‘Digital Orphans’. In it, he compares two approaches to authoring code: The ‘classic’ approach, where code is crafted by hand, and the ‘vibe coding’ approach, where a human simply instructs an AI agent to generate code via natural language prompts and usually does not even look ‘inside’. Adam uses the beautiful metaphor of the parent-child relationship, which is applicable to the relationship between a programmer and their code. This relationship is certainly broken when we ‘instruct’ AI to write and deploy something that works. AI-generated applications become ‘digital orphans’, meaning nobody feels truly responsible for them. This leads to nasty things such as security issues and legacy code being created from day one.

When I thought about it, I said to myself, “Well, that’s certainly true!” But then, almost instantly, I thought, ‘Wait a minute! This is nowhere close to my experiences or how I feel about AI!’

The Vibe Coding myth

In one of my previous articles on Vibe coding, ‘The Rise of Vibe Coding’, I prototyped an experiment to show whether this technique could effectively replace classical coding. At the same time, I expressed my fear that the term ‘vibe coding’ would end up where all the earlier misunderstood or misused IT concepts ended, such as EJB, SOA and Agile.

Let me just cite Andrej Karpathy:

There’s a new kind of coding I call “vibe coding”, where you fully give in to the vibes, embrace exponentials, and forget that the code even exists. It’s possible because the LLMs (e.g. Cursor Composer w Sonnet) are getting too good. Also I just talk to Composer with SuperWhisper so I barely even touch the keyboard. I ask for the dumbest things like ‘decrease the padding on the sidebar by half’ because I’m too lazy to find it. I “Accept All” always, I don’t read the diffs anymore. When I get error messages I just copy paste them in with no comment, usually that fixes it. The code grows beyond my usual comprehension, I’d have to really read through it for a while. Sometimes the LLMs can’t fix a bug so I just work around it or ask for random changes until it goes away. It’s not too bad for throwaway weekend projects, but still quite amusing. I’m building a project or webapp, but it’s not really coding - I just see stuff, say stuff, run stuff, and copy paste stuff, and it mostly works.

Source: Andrej Karpathy on X

I must admit that I do exactly the same since I started using the AI Agent for coding. I always accept all changes, blindly clicking ‘run’ on tools (because GitHub Copilot always asks for confirmation — nobody knows why) and typing ‘continue’ when the agent reaches its internal limits. I didn’t know that Andrej wrote exactly this, but I started using this approach anyway because, honestly, there is no other choice. The reason is very simple: if you do otherwise and review every single line of generated code, check everything against the library API documentation, etc., you’ll end up being as slow as before, except you’ll have to pay an extra fee for the tool and tokens. It’s an either-or situation.

The problem is that you can still generate junk that pretends to work, which cannot be relied on, and this is definitely not what clients pay for. So, for mid-to-large-size custom applications, there must be a way to use the advantages of Vibe and still steer your ship in the right direction.

I am certain that the enterprise story of Vibe coding will follow this pattern: first, there will be an era of naive Vibe coding that generates a lot of legacy code (remember the term ‘green field legacy’!). Then there will be an era of ‘controlled Vibe coding’, whereby for every n young Vibe coders, there will be m senior code reviewers checking each line of code committed twice. Let’s try to avoid that being the end of the story.

(But seriously, I once worked in a company that rolled out ‘controlled agile’!)

There is one problem with the term ‘vibe coding’. It has most likely been misunderstood. Andrej didn’t write ‘You don’t need to be a software engineer to vibe code’. Nor did he say ‘anybody can now write code’. This conclusion was drawn from the words ‘forget that the code even exists’. However, I assume that Andrej Karpatky is well aware that the code exists anyway. As a very experienced programmer, he always imagines what it might look like.

I suspect this because this is how I feel about my experience with this very technique. For me, it’s enough to see the names of the generated or modified files. I take a quick look and know that it is most likely what I was expecting, so I decide not to look at it. And I accept it. I have realised that this is not a ‘blind’ action. I know what I am doing. Even if there is a problem, I will be able to spot and fix it (most likely by prompting the AI again, as I am also getting lazy). This intuition is derived from my skills and experience. Someone with no knowledge of programming would not be able to do that.

AI generated code does not need to be ‘random’

If you use tools such as Cursor, Windsurf or GitHub Copilot, there are plenty of options available to customise the way the AI agent behaves and generates code. In fact, this is not just an option — it’s a necessity. In Copilot, you must provide a file containing the necessary information about the project, its architecture and composition, and the available tools and how and when to use them. You can specify all of this in natural language. It’s even in the manual.

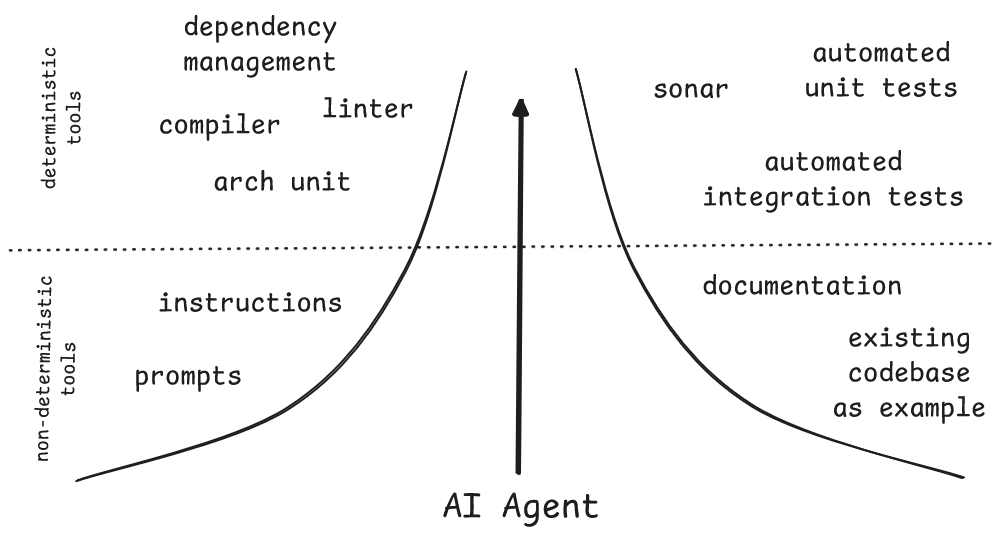

While I am currently pitching Agentic SE topics quite frequently, the question that is always asked is, ‘Can we trust the quality of the generated code?’ My answer is always, ‘You can’t just let Agent do whatever it wants; you have to narrow the corridor’, and then I show this picture:

Narrow the corridor

Narrow the corridor

It speaks for itself. Always.

So, you still need to know how to use and combine these tools effectively. You have to maintain this orchestration. You must ensure that your CI is strict. Everything must be automated. Even testing.

Someone without a programming or engineering background could never do this.

I am not the father of my code

The conclusion I have come to in this rant is actually quite sad. I have realised that I don’t feel any emotion towards the code I write for a living. Well, maybe two or three times, I was exceptionally proud of something I had hand-coded at a very low level. In my whole career. This is not what I expected when I decided to become a programmer in 1990. At that time, I wrote code for fun for the next 10 years. Mostly video games or graphical programs (yes, I loved creating UIs).

Then I decided to become a web developer — a full-stack developer — originally coding in Java, then also including JavaScript frameworks to free myself from the hell of JSP/PHP/JSF. For many years, the code I have written has been for business apps, usually a mixture of CRUDs and some deeper modules, and the UI is usually tables and forms. Perhaps charts, but that’s it. Writing this kind of code is not fun at all. I feel no emotion about it. The only link is visible via ‘git blame’.

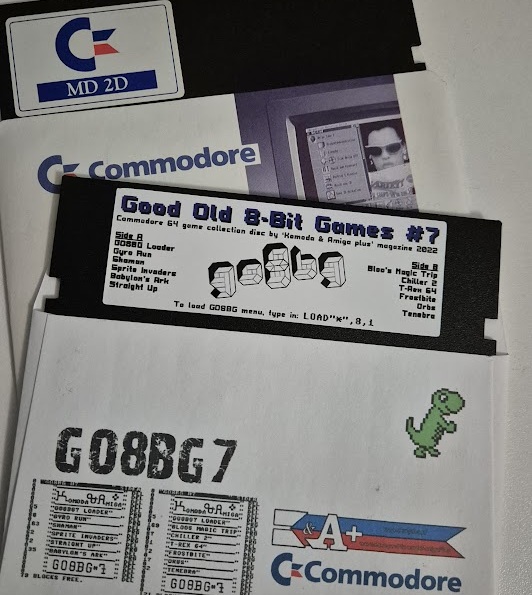

The parts I love are on these disks:

The first one contains a BASIC program that I wrote in 1993 — the only one that survived. It doesn’t do anything particularly useful, but I invented and typed it myself that year. I would show it to you, but I don’t have time to set up my 1541 to read this disk — I know it works. The second one is the first physical release of my video game, a single file on Side B of the disk named TRex64. I write this for fun, spending as much time as I need on it. I coded this in bare assembly. I am the father of this code.

I don’t know anyone who loves coding endless CRUDs, tables and forms. I don’t think anyone cares about code like that (even handwritten) any more than is enforced by CI/CD pipelines. The tools. These are the same tools that AI must use to obey and tackle feedback, correcting itself.

Can an AI agent generate insecure code? Sure! But the same applies to humans.

Can an AI agent generate legacy code from scratch? Oh boy! But existing legacy code has been created by humans! In my whole career, I’ve met at least a few programmers who were writing pure legacy code from day one. Nobody’s perfect.

I am still the father of my architecture

I said that I don’t enjoy coding any more. That’s not entirely true. I don’t think low-level coding is a wonderful challenge nowadays. However, at least 10 years ago, though, I discovered something more exciting. Applications have architectures. Applications can be modularised. We can manage dependencies between modules and the granularity of the modules. Architecture exists on micro and macro levels. We have large, interconnected systems of applications. We have microservices. We can design the architecture to ensure the software remains maintainable in the long term. You know what? Architecture is still relevant, even more so when using Agentic AI for coding.

Can agents create and manage architectures? Of course they can. However, specifying the prompt to do so may reveal the architecture itself, meaning AI could simply confirm our choices. We will still do most of the work ourselves. I am a bit more optimistic about this.

Conclusions

- If we interpret ‘Vibe Coding’ as a way of giving the AI agent some level of trust, we can work with natural language in almost all cases.

- We can gain insight into the way the agent behaves through proper customisation and tool usage.

- A properly constrained agent can work no worse than humans.

- We — humans — can now focus on more interesting aspects, such as the structure of our projects and their architecture, while letting the agent implement loops, ifs, getters and setters.

- Even with AI agents, writing code will remain expensive, but perhaps two or three times cheaper than it is now.

- We still need engineering and programming skills to work with AI agents.