Significance of Architecture

When interviewing new candidates for the software architect position, I like to start with a few awkward questions, such as “What is architecture?”, “Who is an architect?” and “What do you do?”, before waiting for the ensuing moment of disbelief and long silence. Maybe some of them will try to beat the system by using these two rectangles and a barrel. Yes, I was there too.

There are perhaps two reasonably correct answers to these questions. By “correct”, I mean “simple”, because a simple question deserves a simple answer. The first is that the architect is the most senior person on the team and knows about the things and how to avoid the traps. It’s just common sense. However, this answer doesn’t address the question of “architecture”, so we still don’t know what “software architecture” is.

Suprisingly you ask for an architecture and you always get this in response. / Ted Neward in Geekon/Kraków/Poland, 2019

Suprisingly you ask for an architecture and you always get this in response. / Ted Neward in Geekon/Kraków/Poland, 2019

The second correct answer is that “an architect manages the architecture”. Architecture is a system that helps to keep the development and maintenance costs of software at a reasonable level.

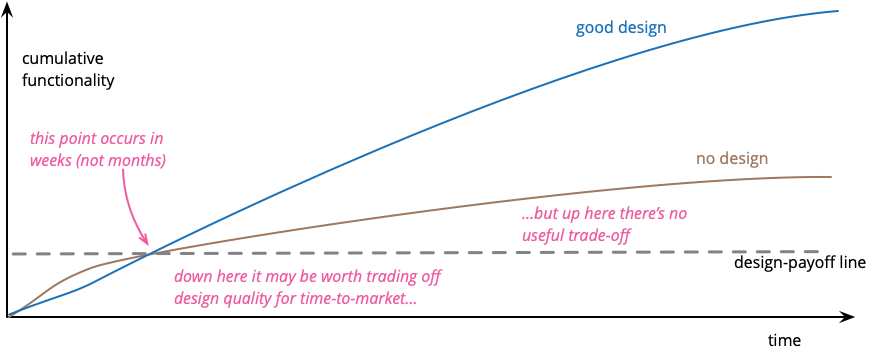

Martin Fowler’s post on design stamina is spot on. Good design — or “architecture”, as it’s also known — is an investment that takes time to pay off. You might not see the full benefits at the start of your project, but over time, the positive effects will become increasingly apparent. At some point, you reach the design payoff line and start producing work at an incredible rate. Then you know that your architecture is good enough.

Fowler’s design stamina chart.

Fowler’s design stamina chart.

There’s a pretty straightforward reason why architecture is important and how it actually works. It’s all down to human nature and the fact that our brains have limited capabilities. With all the lines of code and files these days, plus all the design patterns and technical stuff, it can get really confusing really fast. And it’s clear that it costs money. Either it takes longer and longer to understand the code that needs to be modified, or any changes introduce bugs that have to be corrected. In both cases, you just end up delivering slower, and nobody’s happy about it. In my 23 years in the business, I’ve seen this so many times. Sometimes the code was all mine…

In addition, you see that writing software is actually a team effort, with different team members joining and leaving the project as time goes on. So, the foundation and the guidelines for the architecture are important, because they keep the project alive. Believe me, you don’t want to end up with this extra level of freedom because of different cultures, skill levels and creative approaches, but you do need some standardisation. It’s not exactly sexy, but it works.

A random architect Friday night, resting after another week of fighting with the code. / Apocalypsed

A random architect Friday night, resting after another week of fighting with the code. / Apocalypsed

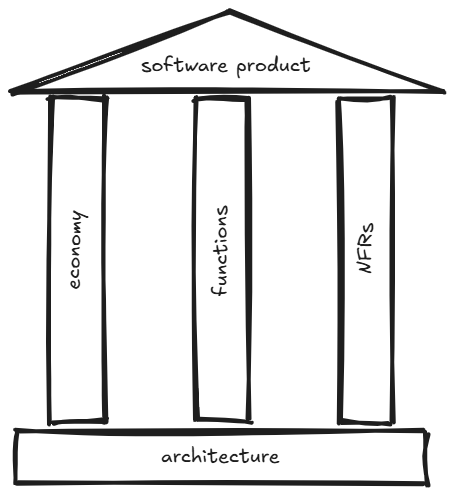

Let’s take a look at how modern software should be constructed. The long-term goal of keeping development and maintenance costs reasonable is achieved by establishing a software architecture, which forms the basis of an economic pillar. There are two other pillars: the second is obvious — providing the required functionality — and the last one, which is often overlooked, comprises a set of non-functional requirements, i.e. industry standards that are not explicitly demanded but are usually essential, such as security, monitoring and performance. NFRs are sometimes overlooked, as is the economic side of development, particularly by green field specialists who prefer to start a new project and then hand it over to a software-house-powered team for “maintenance”. I’ve experienced this too.

Acropolis of the software engineering

Acropolis of the software engineering

I have deliberately excluded the economy part, even though I could translate it into maintainability and, like all “abilities”, easily squeeze it into the NFRs section. However, clients rarely explicitly request this kind of economy (unless you do T&M). In fact, it is almost always the deliverer’s responsibility to ensure the project has the right margin.

Another aspect is developer sanity. This is the responsibility of the developer, as clients do not care. There is a clear connection between the design of software architecture and the pleasure of coding, as well as the mental health of developers who are forced to struggle with sequences of characters forming computer programmes. This soft factor may greatly affect job rotation and project efficiency.

Listen my son. I have built this software on a swamp. It sank into the swamp. So I built a second one. That sank into the swamp. So I built a third. That burned down, fell over, then sank into the swamp. But the fourth one stayed up. / Monty Python and the Holy IT Architecture

Listen my son. I have built this software on a swamp. It sank into the swamp. So I built a second one. That sank into the swamp. So I built a third. That burned down, fell over, then sank into the swamp. But the fourth one stayed up. / Monty Python and the Holy IT Architecture

But does architecture still matter in the year 2025? This is a pertinent question at a time when more and more coding tasks are being taken over by AI. Is architecture a human domain? If we eliminate humans, will it still be needed? AI never gets tired and, as time goes on, it will probably become cheaper and cheaper. It is unlikely to become mentally ill.

To answer “yes” here, one must assume that AI does not really have comprehension limits. Furthermore, code without architecture can easily exceed polynomial complexity in terms of execution paths. Tireless AI could facilitate this growth by producing an increasing number of PRs. If we cannot see the limits of AI now, would that still be the case after several iterations?

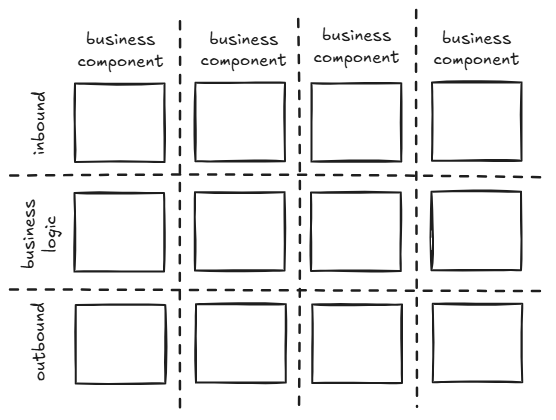

So-called clean architecture prioritises good concern separation, i.e. vertical separation into modules or business components and horizontal separation into layers. It treats inbound technical concerns, business logic and outbound technical concerns separately. Each rectangle then represents an easy to comprehend piece of code.

So-called clean architecture prioritises good concern separation, i.e. vertical separation into modules or business components and horizontal separation into layers. It treats inbound technical concerns, business logic and outbound technical concerns separately. Each rectangle then represents an easy to comprehend piece of code.

Unless it is proven otherwise through empirical evidence, we cannot assume that AI will be able to work reliably with a complex codebase. So, if we don’t know that for sure, we cannot just let vibe in. It will most likely end up in a disaster.

From my own experiments, I have noticed that a certain degree of order (architecture) actually helps AI produce better code and understand the existing code base more deeply. Good modularity (vertical separation) also helps AI build context properly and match the developer’s prompt to the right elements of the code base. Horizontal separation (concern isolation) reduces informational noise in code, enhancing the models’ comprehension capabilities. In short, if it’s easy for the human brain, it’s also easy for an artificial brain — perhaps because modern AI still tries to mimic real-life neural structures.

Another important aspect is the concept of “human in the loop” — in other words, the role of the human operator (software developer) in controlling and orchestrating the development of new features by AI. Architectural restrictions help such people to understand this huge amount of generated code; otherwise, blind acceptance will always lead to destruction.

I strongly believe that IT architecture is far from obsolete and must remain a cornerstone of the GenAI revolution. But who knows what will happen in the next six months?